This (picture heavy) post is a follow-up to Part I, and covers the next phase of installing an authentic tudor roof. As always, I welcome your feedback. It gets a little lonely, here, sometimes!

A view of the ceiling. There are a few little bits hanging out, but I'm not too concerned at the moment. I'm going to touch up the inside, and deal with any problems, when it comes time to cut, finish, and install the interior support beams.

Another view of the ceiling.

I dry-fitted some of the paneling, to get the general effect.

A close up of the fabric. You can see what I mean about it having a "direction". It looks and feels like mossy bark. Scale is a critical issue, here; small scale "bark" and "moss" don't look the same as our full scale stuff.

I find it helpful to cut out a pattern, first. This helps save aggravation...and fabric! This is the back view of the fabric.

I trimmed the fabric with a (very sharp) x-acto knife, before attaching the wood trim.

I ran extra pieces of fabric around the underneath of all the overhangs. It's important, here, to remember that all the fabric pieces point the same "direction"! This is really one of those situations where the final product is more than the sum of its parts. No, it doesn't look very realistic now...but it will.

I repeated the same procedure with the front, as I did with the back.

I found it easiest to tape the overhang in place, allowing the glue time to dry, before trimming it to fit.

Our little eyrie is getting somewhere!

Fitting all the eaves with fabric is a super tedious process, but completely worth it in the end.

I (carefully) patched holidays with tiny extra bits of fabric.

A view of the inside, with the edges all trimmed.

I waited until after I'd trimmed all the edges, and applied the basswood facing, before applying stain. The stain I'm using on the exterior is a raw umber. After the stain dried, I applied two thin coats of satin varnish. Here, the varnish serves a dual purpose; I gently went over just the edges of the fabric with varnish, to keep it from unraveling. Little bits and pieces of fabric poking out is desirable; this is, after all, supposed to be made of bark and sod--a little mess is realistic. However, you don't want pieces of fabric hanging out all over the place--or, indeed, unraveling completely over time.

Another view of the finished edging.

A close-up of the varnish bead.

Another close up of the varnish bead.

The reason it's important to carry the fabric all the way around is, this roof is supposed to be as authentic as possible. In real life, the whole thing would've been made of a various combination of planks, bits of bark, bundled rushes, and/or sod.

The cats eventually got bored of watching me and decided to take a nap on top of the radiator cover.

OK, now we're ready for the second phase of this roof. No tudor ceiling is complete without interior beams. Particularly, too, with fabric like this, you need mixed media to break up the patterns and textures, and make the final product seem a little more authentic. I began by selecting a slightly smaller piece of wood for the interior beams. In a real tudor home, many different beams of many different dimensions were used, depending on their intended function--and, of course, on the amount of weight they were meant to bear. Using the same size wood, exclusively, will both bring your house out of scale, and look inauthentic.

I dry-fitted the interior beams. For this project, I decided on five beams. You can see, in this close up, one consequence of using fabric: a buckle, directly above the right-hand beam. I solved that problem by making a small incision--along the "direction" of the fabric--with my x-acto knife, daubing in some blue, and pressing the buckle flat.

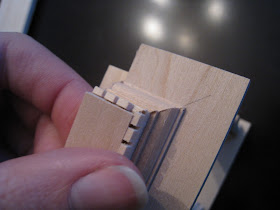

Because the beams require a bit of a funny angle, it's important to dry-fit them.

Here, I'm testing the beams out for length. I cut the steep angle first, because it's the most challenging, and then pressed the beams toward the ceiling, to determine the exact length. It's better to start out slightly too long, and shave down, than start out too short and waste wood.

After I dry-fitted the beams running along the far ceiling, I cut and dry fitted the beams running along the near ceiling. In my house, these latter beams slightly overlap the first set. For authenticity's sake, I wanted everything to fit together as perfectly as possible, so I made a lot of fine tuning adjustments. It was stressful, yes...but really rewarding at the same time.

Oh, and hey...in case you're wondering, "what are those pegs, and that hanging chair about?", I was inspired by American Amish architecture. The Amish are tremendous believers in utility, and we can all learn a lot from them. The American Shaker movement certainly did; many authentic Shaker homes, and public buildings, feature the same system of pegs. Basically, the Amish hang everything from chairs, to side tables, to quilts on the wall, when they're not being used. The idea is to get them out of the way, so the room can be put to as many different uses as possible. When friends come over, you can take the chairs down off the wall; after they leave, you can hang the chairs back up and use the open space to lay out quilt pieces.

Since this is a fantasy dollhouse, I borrowed these indigenous American elements. Actually, if you look closely, Peter Jackson did something quite similar when he conceived the film version of Bag End. Amish, Shaker, and Tudor elements blend a lot more elegantly than you might at first assume! Because my little hut is so small, I wanted to furnish it with more delicate furniture. These chairs were purchased at a show from Pete and Pat Boorum of Smaller Than Life. They make many wonderful pieces, all of which exhibit extraordinary craftsmanship. Simple furniture relies on proportion to achieve beauty, and their furniture is unusually elegant.